ROCHESTER, NY: INNER LOOP AND REMOVAL

Posted December 3, 2025

Rochester, NY, before-and-after construction of the “Inner Loop” highway; and before-and-after the first phase of the highway’s removal in 2014-17, which started the process of reconnecting the neighborhoods the loop had long separated from Downtown. The removal serves as a model for other cities looking to address the racist legacy of highway construction and urban renewal. “This is not just transportation,” said Erik Frisch, special projects manager for the city. “It is focused on racial equity, healing old wounds and making sure that current residents and residents that were displaced will benefit.” [1]

The history of the Inner Loop is an almost prototypical case of “segregation by design.” As in cities around the country after WW2, Rochester leveraged federally-funded highway construction and “urban renewal” projects to achieve the dual goals of (A) in the context of postwar white flight, improving connections between the growing whites-only suburbs and employment opportunities in the city’s commercial core, and (B) in the context of the ongoing Great Migration and the growth of the city’s Black population, physically removing or containing neighborhoods with populations viewed as undesirable and detrimental to property values. [2]

Construction of the Inner Loop achieved these aims by creating a literal moat around Downtown, designed to protect the commercial core from the encroachment of the “inner-city” neighborhoods that surrounded it, while simultaneously providing improved automobile access for suburban commuters. Thousands were displaced [3], and the formerly continuous street grid was replaced with a haphazard series of overpasses that prioritized regional over local accessibility. [4]

Ultimately, throughout the 60s and 70s employment also followed white residents to the suburbs, leaving Rochester with an overbuilt highway network surrounding a hollowed out Downtown [5]. As the highway’s structure decayed in the early 2010s, NYSDOT faced a choice: modernize the structure and make the division permanent, or remove it and reconnect the city. Pressured by decades of local advocacy, the city has chosen the more equitable path.

Phase 1 started with removal of the eastern portion of the highway and is seen at the end of the video above. Almost all traces of the former highway route were removed , replaced with a reconnected street grid and infill mixed-use development, including hundreds of units of multi-family affordable housing (see the site here on google maps). The area remains a work in progress, but removal has undeniably been a success (at least in economic terms): new housing and commercial space has been filled, and the area only continues to see further infill.

While this first phase is promising, it is not a perfect lesson for other cities to draw from, especially in cities in which gentrification is a concern. Some in the neighborhood criticize the design of the new housing, noting that it has formed a visual wall between Downtown and the surrounding neighborhood, and are rightly skeptical of the developer-driven construction process [6]. Furthermore, compared to the planned Inner Loop North Removal Project (the second phase), the Inner Loop East Removal project (the completed portion) affected an area more commercial than residential, creating less risk of gentrification resulting from the significant public investment.

The Inner Loop East project (the first phase) did not raise as many concerns about displacement because it affected a downtown area with fewer residences, says Frisch to the Rochester Beacon. “So when you get into Inner Loop North [the second phase], especially in the Marketview Heights area, you have different concerns. You are talking about an area that very clearly was a lower income and highly nonwhite population that existed prior to its construction. …. A lot of people have lived there for generations and are still there and can still feel the wounds caused by the construction.”

Continued from the Rochester Beacon:

In the wake of this history, Frisch says, the city government is trying to embed community input into the development of the Inner Loop North Transformation Project to rebuild public trust.

“We fully appreciate how the construction of the highways, combined with the redlining that was occurring at the same time, contribute to a complete lack of trust in what the government is doing,” he says. “When we come in here and we say, ‘We’re going to make everything better.’ I can totally understand why people would say, ‘Really? We’ve heard this before.’”

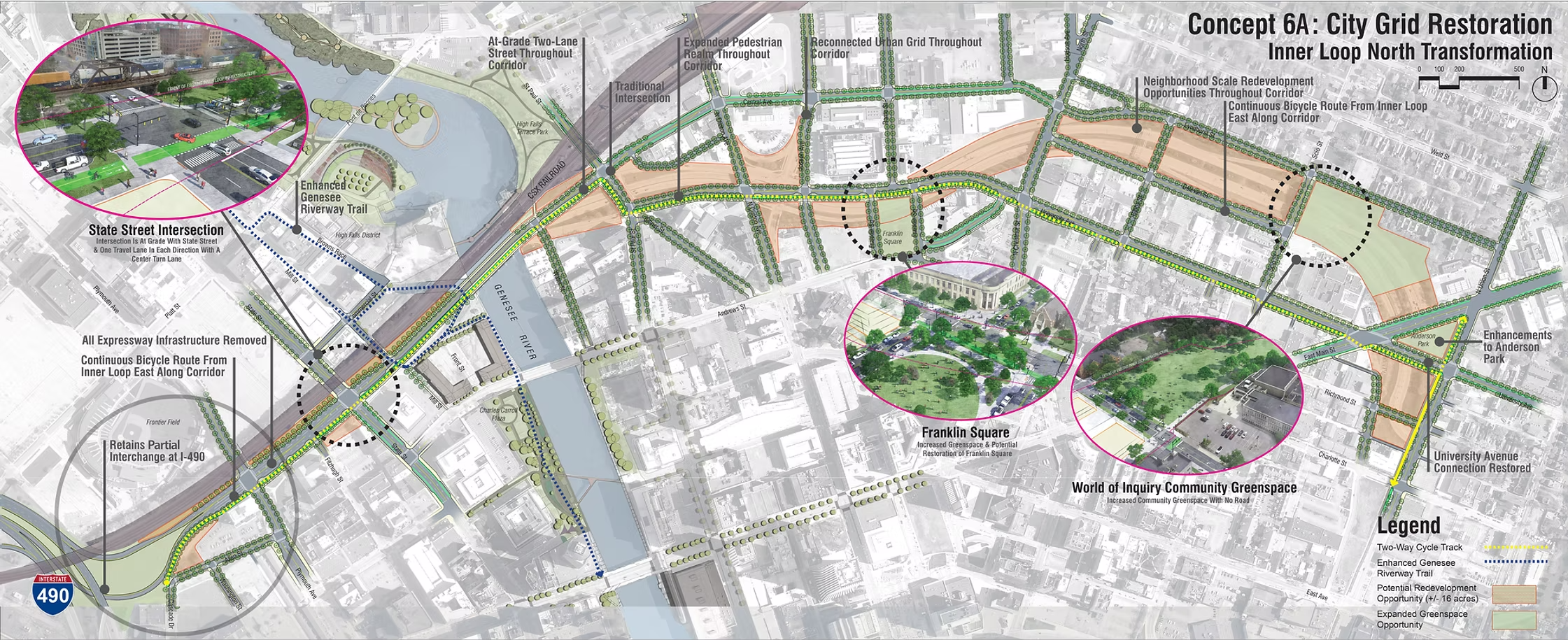

For instance, when the city was floating concepts for the project last year, officials offered a range of six levels of restoration and asked the community to weigh in via online voting or in-person voting at the four meetings they held. The community opted for Concept Six, which promised the greatest degree of restoration, and the city turned this into the current concept moving forward, Frisch says.

Frisch says Marketview Heights residents have adamantly demanded lower-density, owner-occupied, and affordable housing. “We want people to have opportunities to own homes, but we also want people to not be displaced from the homes that they’ve been living in,” he says. “So, we’ve got to find that right mix, that right balance.” [7]

The need to strike this balance is critical, as even more than the first phase, the Inner Loop North Removal will be a true test of “reconnecting communities.” While a limited number of cities have had success with highway removal (and, indeed, all American cities should be considering it for at least portions of their network), much less common have been large-scale urban infrastructure projects that prioritize the needs of existing urban communities over the capitalistic drive to extract as much financial value as possible from the development enabled by public investment [8].

Highway removals, caps, and other infrastructural transformations certainly have the potential to “reconnect communities” (along with a host of environmental and mobility benefits), but they also have the potential to precipitously gentrify, displacing the very communities they sought to serve. [9]

Thus it is promising to see officials such as Frisch taking community input so seriously, as well as the continued construction of affordable housing. It is also promising to see the selection of Concept Six, the most thorough removal option. Concept Six reconnects the street grid as it was before highway construction, restores historic park space that was lost, and, hopefully, will allow for the equitable restoration of the neighborhood.

As of now, the project is mostly funded and the design phase continues. Stay tuned for more updates. Also see the project website here. Follow Hinge Neighbors (@hingeneighbors), a coalition of Rochester residents advocating for the community through the design process, for more. Also Reconnect Rochester for equitable mobility advocay (@reconnectroc).

Endnotes

Sharp, Brian (2021). “Will plans for Inner Loop heal historic wounds or continue legacy of inequality?” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. (@democratandchronicle). https://eu.democratandchronicle.com/story/news/2021/10/13/inner-loop-rochester-ny-impact-on-neighborhoods/8137874002/ (accessed 2 Dec 2025).

Archer, Deborah N. (2025). Dividing Lines: How Transportation Infrastructure Perpetuates Racial Inequality. W.W. Norton. (@deborahnarcher).

“Clarissa Uprooted: Unearthing the Story of Our Village.” Clarissa Uprooted. (@clarissa_uprooted585). https://www.clarissauprooted.org/ (accessed 2 Dec 2025).

Thompson, Brennan (2017). “Race and Place in the Flower City: A Case Study of Perpetual Marginalization through Urban Planning.” Medium. https://medium.com/%40bt8002a/race-and-place-in-the-flower-city-300e8aac4d07 (accessed 2 Dec 2025).

Katz, Bruce (2008). “A Two Percent Solution for Downtown Rochester.” Brookings Institute. (@brookingsinst). https://www.brookings.edu/articles/a-two-percent-solution-for-downtown-rochester-ny/ (accessed 2 Dec 2025).

Byrnes, Mark (2024). “What Happens After a Highway Dies.” Bloomberg Citylab. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2024-04-13/rochester-s-inner-loop-project-shows-what-happens-after-a-highway-dies (accessed 2 Dec 2025).

O’Connor, Justin (2022). “Inner Loop North Project is a Balancing Act.” Rochester Beacon. https://rochesterbeacon.com/2022/03/30/inner-loop-north-project-is-a-balancing-act/ (accessed 2 Dec 2025).

Susaneck, Adam (2023). “How to Reconnect Neighborhoods, and How Not to.” Transportation Alternatives. (@transportationalternatives). https://medium.com/vision-zero-cities-journal/how-to-reconnect-neighborhoods-and-how-not-to-c4cb0f719664 (accessed 2 Dec 2025).

Patterson, Regan and Harley, Robert (2019). “Effects of Freeway Rerouting and Boulevard Replacement on Air Pollution Exposure and Neighborhood Attributes.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. (@reganf.p). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31652720/ (accessed 2 Dec 2025).