DETROIT: CORKTOWN

Posted October 3, 2025

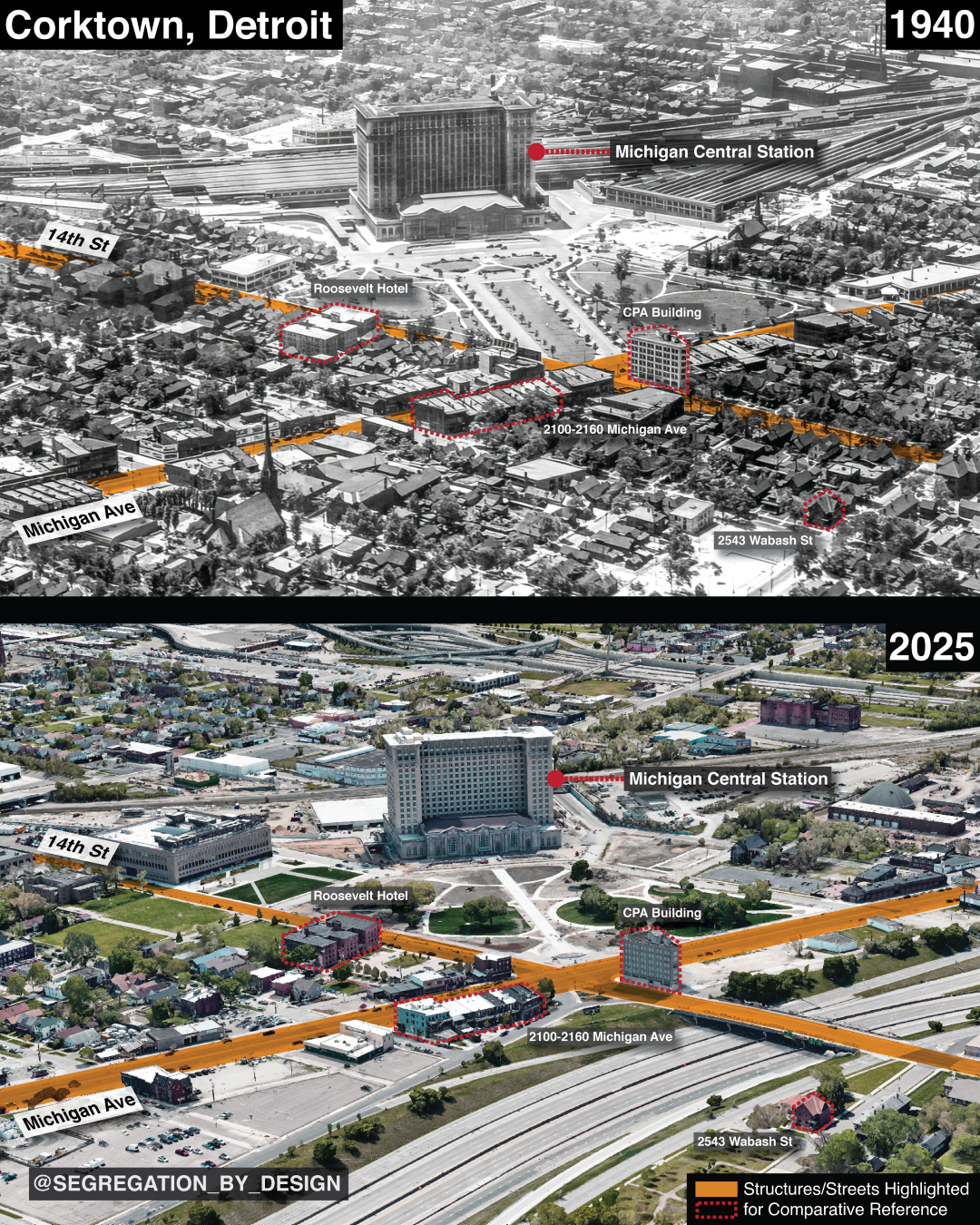

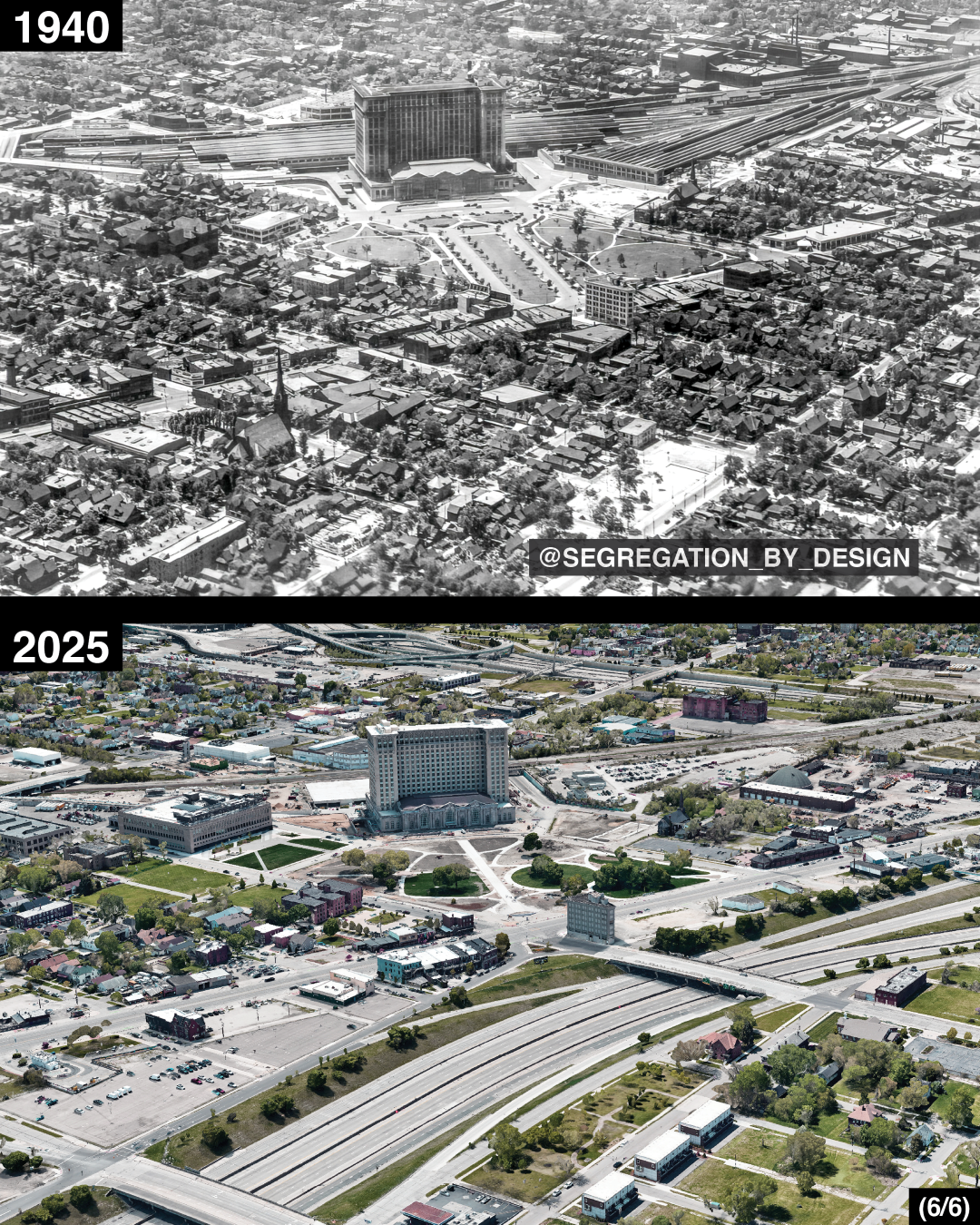

Corktown, Detroit, before-and-after federal highway construction and “urban renewal” in the 1960s and 70s, which leveled much of the neighborhood and displaced thousands of residents.

Initially home to Irish immigrants fleeing the Potato Famine of the 1840s, by the 1920s the growth of auto-industry jobs had brought immigrants to the area from all over the world, in particular Mexico, Malta, Poland, and many others [1]. By the 1950s the neighborhood’s Most Holy Trinity Church was the city’s largest Latino parish, serving the significant Mexican population [2]. The area was also home to a sizable Mohawk Indian population [3] and a small but growing number of Black residents north of Michigan Ave [4].

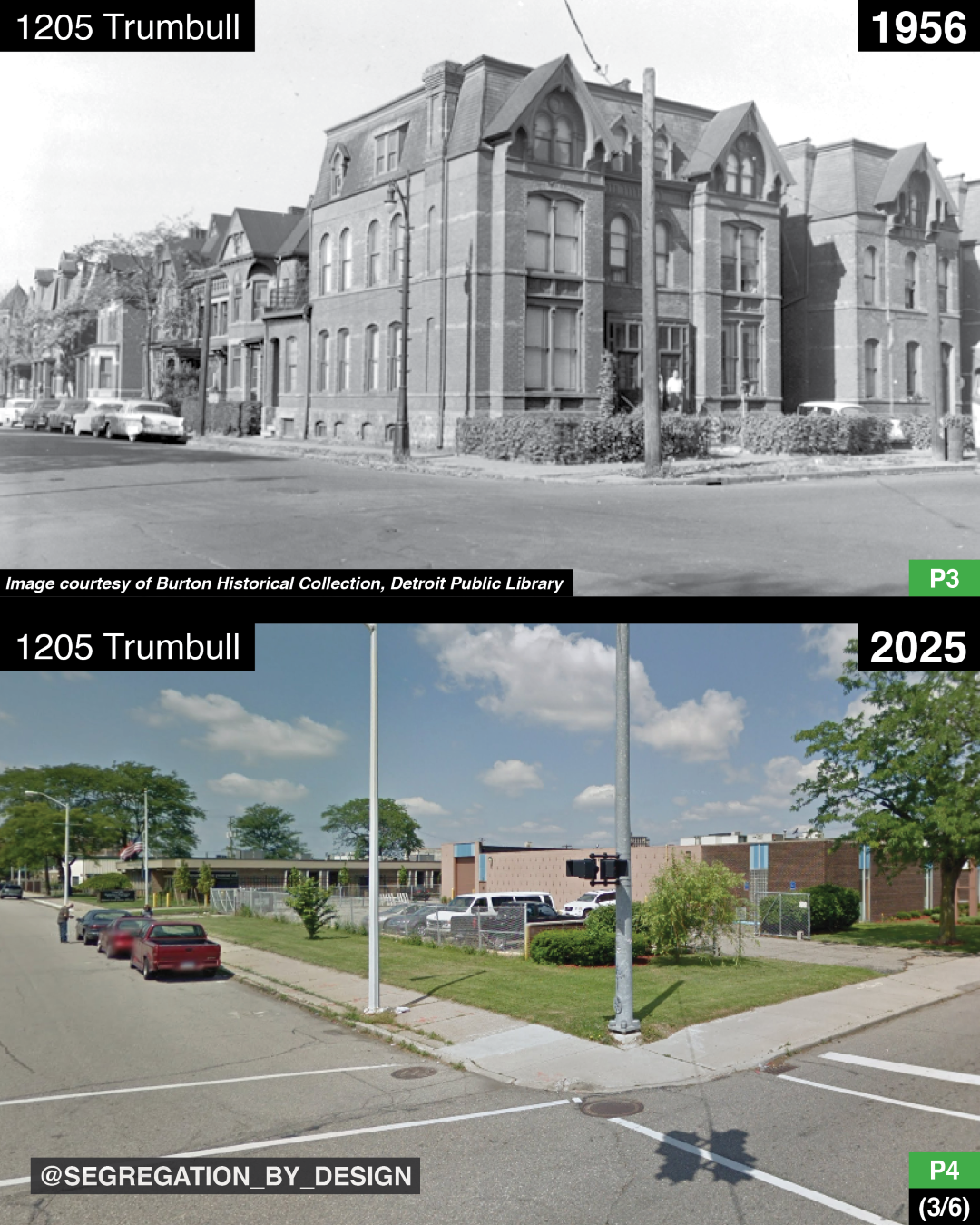

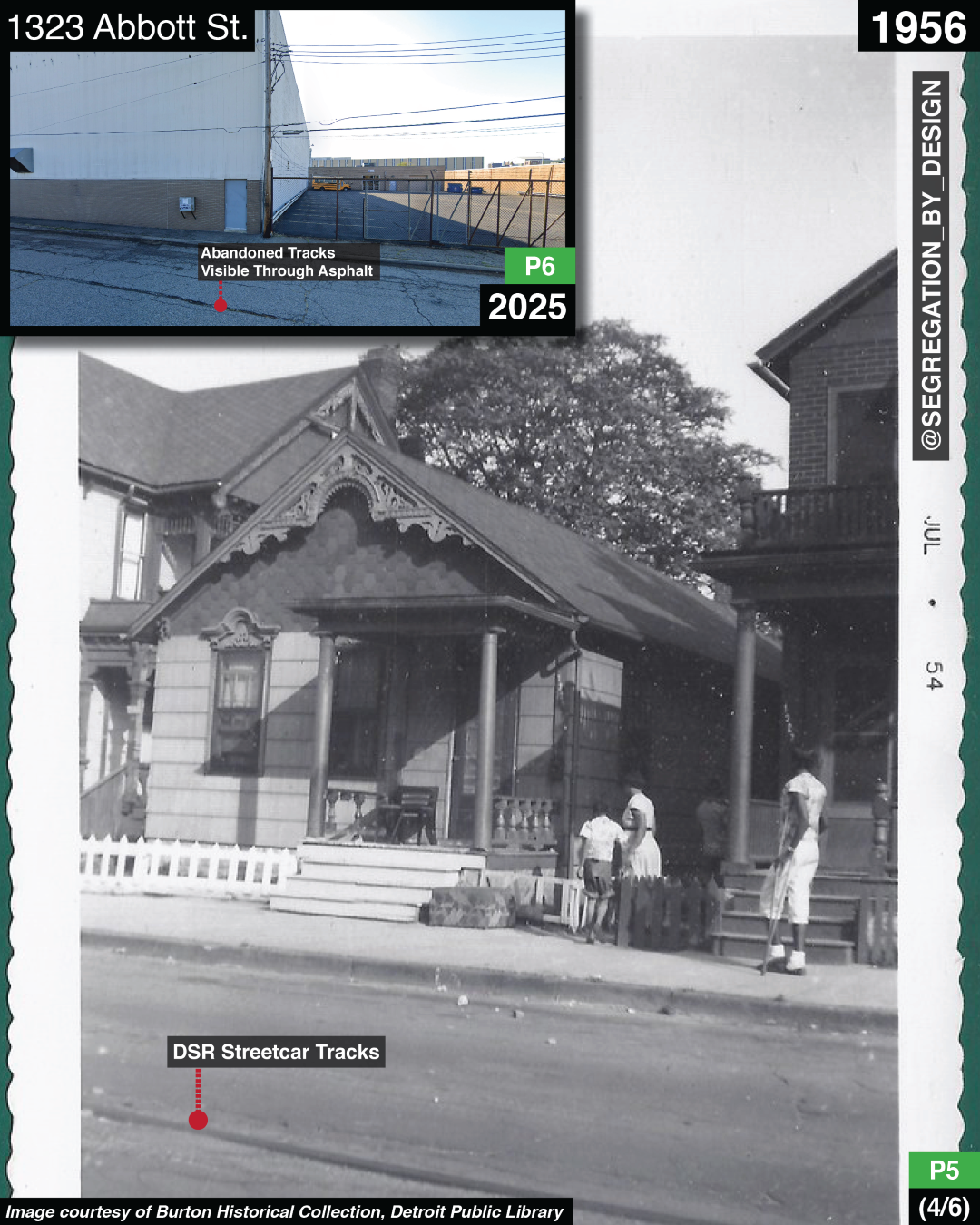

The 1930s redlining map describes this population as a “heavy concentration of low grade aliens,” derisively noting that the area is a “‘melting pot’ - 15 nationalities.” Despite the neighborhood’s stately Victorian housing (images 2-4), the redlining map notes “type of population rate the area 4th grade” [5]. By restricting residents’ access to financial services and discouraging investment, redlining precipitated the area’s physical decay. Combined with this policy-driven disinvestment, because of Corktown’s proximity to both international crossings to Canada (the MCRR railway tunnel and the Ambassador Bridge) and to existing industry (the GM Assembly facility), city leaders had long eyed this primarily-residential area for industrial redevelopment.

In pursuit of this goal, the city sought to officially label the neighborhood as “blighted” so as to qualify for federal urban renewal funds. Despite residents’ protests, in 1957 the City Council officially condemned the area, with a report claiming Corktown was “unfit for homes” and “cannot be transformed into a good residential area” [6]. Mayor Albert Cobo—who had advocated for the use of highways and urban renewal as a means to clear “blighted” neighborhoods for the purpose of commercial/industrial growth (as happened in Black Bottom/Paradise Valley)[7]—pushed for Corktown’s redevelopment, with much of the neighborhood being razed and rezoned industrial shortly after he left office.

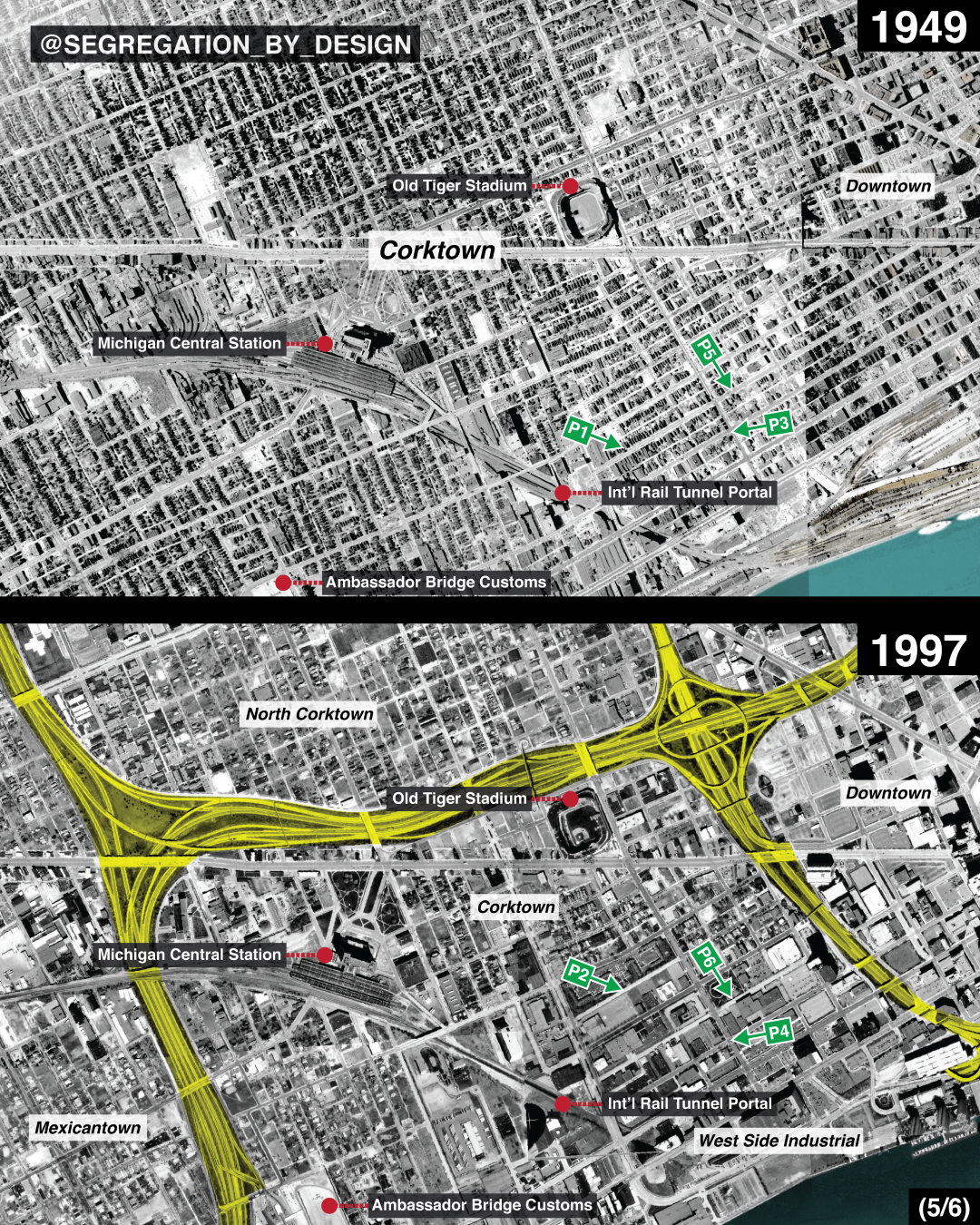

By the late 1950s, much of the neighborhood had been demolished for the creation of the West Side Industrial District, as it was known. At the same time, Corktown had also been divided from Downtown by the federally-funded construction of the John C. Lodge Freeway. After the passage of the 1956 Federal Highway Act, which further boosted federal funding for highway construction, more highways were cut through the area throughout the 60s, dividing the formerly coherent community into several different neighborhoods [8], including Corktown and North Corktown (and with many of the displaced Latino residents moving west to what is now “Mexicantown,” located immediately west of 75 [9]).

Having been nearly entirely surrounded by freeways, as well as having had its streetcar service eliminated (see Detroit Transit post for more), the area became inundated with automobile traffic and pollution. This problem was especially pronounced on Tigers gamedays, with the old Tiger Stadium located on Michigan Ave in the heart of the neighborhood (demolished 2009). As more and more fans drove to the stadium for the dozens of games and events, quality of life in the neighborhood markedly decreased [10].

By the 1970s much of the expected industrial development had failed to materialize, leaving Corktown littered with vacant lots (often filled with stadium parking) and abandoned buildings, fueling a cycle of reduced property values and decay [11]. The expansion of the Ambassador Bridge customs facilities in the 80s and 90s further ate into the urban fabric, and the abandonment of passenger service at Michigan Central Station in 1988 eliminated one of the neighborhood’s final economic drivers.

Ultimately, Corktown is yet another instance of a diverse, working-class neighborhood sacrificed by city leaders in the pursuit of economic growth. The elements that had attracted residents to the area in the first place—the neighborhood’s proximity to industrial and Downtown jobs, and its transportation/international connections—also made it an attractive potential site for redevelopment. This was especially true in the postwar era of white flight, when city leaders like Mayors Cobo (1950-57) and Louis Miriani (1957-1962) were concerned about the increasing loss of population and jobs to the suburbs [12]. Leveraging federal money made available through the 1949 Federal Housing Act and the 1956 Federal Highway Act, City Hall used “urban renewal” and highway funding not to improve the housing conditions of “inner city” residents, but instead to uproot their lives in an ultimately unsuccessful bid to retain some of the city’s industrial base.

For more on Corktown history, check out the Corktown Historical Society. Also check out the work that the North Corktown Neighborhood Association is doing through their community land trust (CLT) to create green space and equitable housing development.

Endnotes

1. Gallagher, John (2018). “Corktown’s History Begins with Immigrants.” Detroit Free Press. https://eu.fareep.com/story/money/business/john-gallagher/2018/07/09/detroit-corktown-history/745668002/ (accessed 9 September 2025).

2. City of Detroit Historic Advisory Board (2023). “Most Holy Trinity Roman Catholic Church.” Historic Detroit. https://historicdetroit.org/buildings/most-holy-trinity-roman-catholic-church (accessed 9 September 2025)

3. “Native American History in Detroit” (2020). National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/native-american-history-in-detroit.htm (accessed 9 September 2025).

4. Lenhoff, Sarah Winchell et al. (2025). “Corktown Residents’ Perceptions of their Neighborhood.” Detroit Partnership for Education Equity and Research. https://detroitpeer.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Corktown-Survey-Report.pdf (accessed 9 September 2025).

5. Nelson, R. K., Winling, L, et al. (2023). “Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America.” Digital Scholarship Lab. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining (accessed 9 September 2025).

6. Szewczyk, Paul (2013). “Ethel Claes and the West Side Industrial Project.” Corktown History. https://web.archive.org/web/20130826102139/https://corktownhistory.blogspot.com/2013/02/ethel-claes-and-west-side-industrial.html (accessed 9 September, 2025).

7. Sugrue, Thomas (1998). The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. University of Princeton Press. Pp 249.

8. Szewczyk, Paul (2013).

9. City of Detroit Historic Advisory Board (2023).

10. “Detroit’s Corktown Neighborhood” (2013). Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University. https://reuther.wayne.edu/node/10375 (accessed 9 September, 2025).

11. “Detroit’s Corktown Neighborhood” (2013).

12. Sugrue, Thomas (1998).