DETROIT: HASTINGS STREET

Posted August 12, 2025

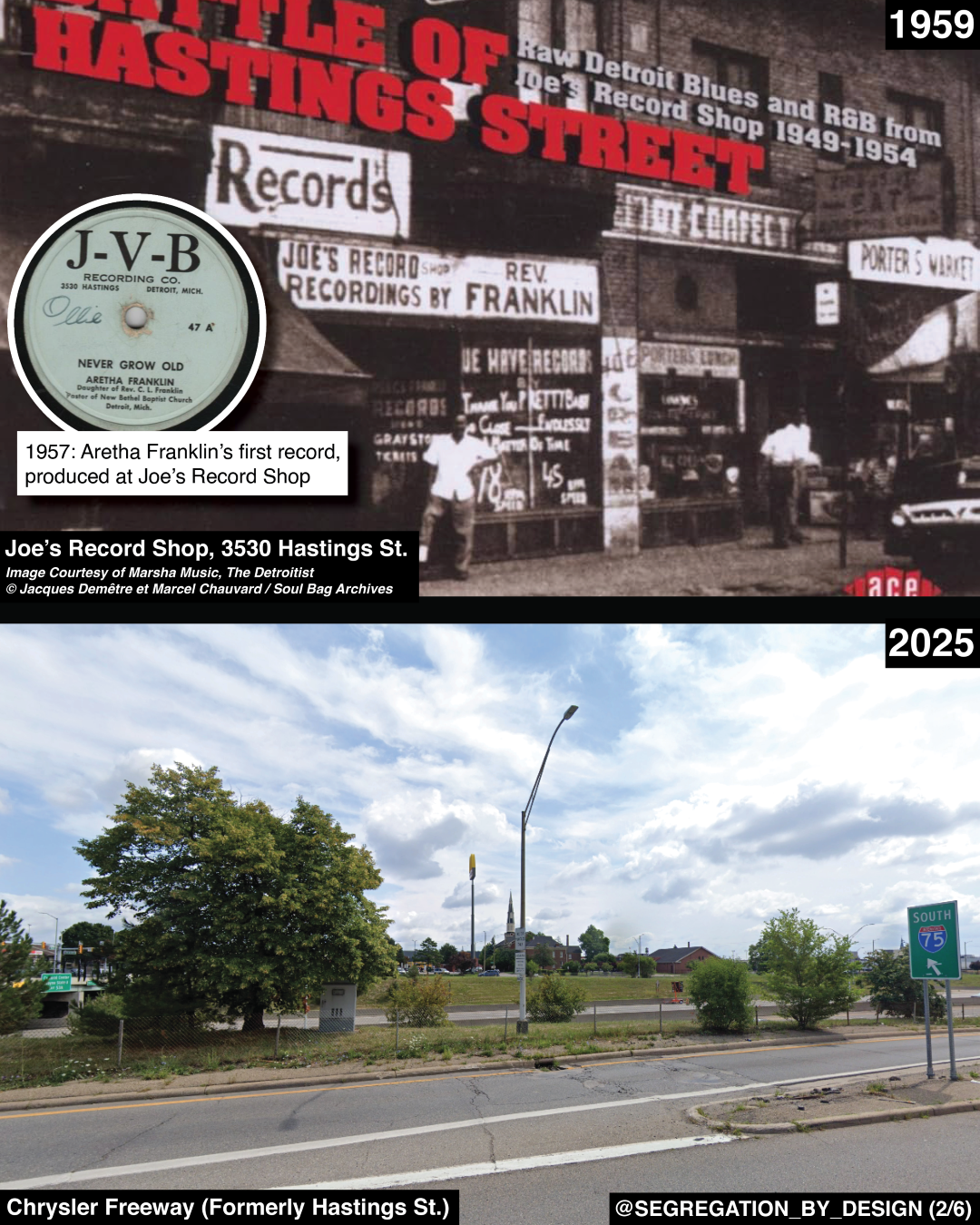

Paradise Valley, Detroit, seen on two album covers that capture the neighborhood before it was demolished for construction of the Chrysler Freeway and “urban renewal” in the 1960s. The albums feature photos taken outside Joe’s Record Shop, which for over 20 years was one of the social and cultural anchors of Hastings St., the main commercial corridor through Black Detroit, before it was destroyed for the freeway.

Prior to the 1960s, the city’s Black population was largely confined to Paradise Valley and the adjacent Black Bottom neighborhood due to racist housing policy, including restrictive covenants and redlining (see I-75/375 post for more)(1). The Detroit Free Press writes: “Given Detroit’s segregation in that era, Black Bottom [and Paradise Valley] were isolated economically and socially, but it became a city within a city, with black merchants, doctors and lawyers living and working in the neighborhood. Its sidewalks were crowded and its blocks were a mixing bowl of classes...Poverty and prosperity co-existed.” (2).

Hastings St. connected the neighborhoods (third image), lined with hundreds of locally-owned businesses, including Joe Van Battle’s legendary record shop (fourth image). Joe’s Records was a neighborhood focal point, a popular hangout for Gospel, blues, and jazz musicians from Detroit and around the country (3). On his record label JVB, Van Battle was the first to record Rev. CL Franklin, the famous preacher known nationally as the “Million Dollar Voice,” and the first to record Franklin’s daughter, Aretha.

Despite the neighborhoods’ growing prosperity, Detroit’s all-white leadership viewed them as a hindrance to economic growth. In the post-war era of white flight, City Hall was concerned that the increasingly non-white population of the “inner-city” would scare away investment, accelerating loss of capital to the suburbs. Leaders like Mayor A. Cobo viewed highway construction and renewal as a means to stem what he called the “negro invasion” (4). Through these programs, he could remove Black neighborhoods, replacing them with highways designed to connect the suburbs with Downtown jobs, expanded institutional space, and upscale housing.

Joe’s Records was one of the hundreds of businesses demolished during renewal, along with tens of thousands displaced from their homes. Van Battle’s daughter, Marsha Music, writes of her father’s experience during this time in her piece, “Joe Van Battle: Requiem for a Record Shop Man”:

“In 1960, after Hastings street was urban renewed into the Chrysler Freeway, my father was forced to move his record shop from the East Side of Detroit to the West, across town to 12th street.

This massive shift was an historic urban migration, uprooting the community–including many Hastings business folks–from their entrepreneurial and residential roots–a destruction of generational wealth from which our community has never fully recovered. Many of them, having already survived the migration from the South, could not withstand yet another traumatic transition, and many African-American businesses were lost forever.

My father would go back to old Hastings St. as the freeway encroached its way North. His shop was gone, but a few holdouts remained, waiting on the wrecking ball. I remember we stood on the banks of the dirt-filled crevasse, the initial diggings of the Chrysler Freeway. My daddy looked across, down into the giant pit, to the place where his record shop once stood, and he shook his head and said, “That used to be Hastings.”(5)

You can read more about Music’s experiences growing up in the neighborhood, the history of her father’s record shop and its impact on the city’s music scene in the complete piece on The Detroitist, https://marshamusic.wordpress.com/

By the late 60s, the entirety of the Hastings corridor was cleared to make way for the Chrysler Freeway (fifth image), and the surrounding neighborhoods were cleared for renewal. The displaced—many of them renters offered no compensation whatsoever for the loss of their homes (6)—were forced to find housing in other, already overcrowded neighborhoods, or attempt to squeeze into limited public housing. In either option, the sudden upheaval of the community and its businesses, combined with the persistence of racist housing policy, has contributed to the racial wealth gap (7).

Furthermore, “Public housing was problematic,” said Detroit historian Jamon Jordan to City Journal. “After years of living there all you would have would be rent receipts.” Because of redlining and other racist housing policies, “African-Americans would get the projects, whites would become homeowners. And property ownership is the way to accumulate wealth in America.” (8).

While public housing could have been and still could be a solution to the significant housing shortage we are facing in the United States, the manner in which it was actualized in the postwar era exacerbated existing inequality. By commodifying housing as an asset for wealth accumulation and subsequently facilitating/promoting white homeownership (through means such as the subsidized mortgages of the GI Bill), while actively preventing others from purchasing homes (through redlining and restrictive covenants), the government and real estate industry created a racial two-track system that was doomed to fail those in the “projects.” While white residents would build wealth through home-ownership in the suburbs, Black residents would be relegated to public housing, which due to the city’s shrinking tax base would deteriorate due to poor maintenance (9).

The largest of these projects in Detroit, the Brewster-Douglas Homes adjacent to the Chrysler Freeway, was itself demolished between 2003-2014 (sixth image). The site is currently awaiting redevelopment. City Journal writes, “Black Bottom, in effect, was cleared again.” (10)

More on the history Black Bottom and Paradise Valley to come—stay tuned. In the meantime, check out the Black Bottom Archives for more on the history of the neighborhood, as well as the Detroit Historical Society.

Endnotes

Rector, Josiah. “Detroit: Context.” Mapping Inequality, Redlining in New Deal America. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/map/MI/Detroit/context#loc=12/42.3532/-83.0503&mapview=polygons (accessed 21 May 2025).

McGraw, Bill (2017). “Bringing Detroit’s Black Bottom Back to (Virtual) Life.” Detroit Free Press. https://eu.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan/detroit/2017/02/27/detroit-black-bottom-neighborhood/98354122/ (accessed 11 June 2025).

Sugrue, Thomas (1998). The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. University of Princeton Press. Pp 249.

Music, Marsha. “Joe Van Battle - Requiem for a Record Shop Man.” The Detroitist. https://marshamusic.wordpress.com/page-joe-von-battle-requiem-for-a-record-shop-man/ (accessed 11 June 2025).

Whitaker, David (2023). “Understanding the Impact of I-375 Construction.” City of Detroit City Council, Legislative Policy Division. https://detroitmi.gov/sites/detroitmi.localhost/files/2023-09/Impact%20of%20I%20375%20ek%202.pdf (accessed 21 May 2025).

Husock, Howard (2021). “Rock Bottom.” City Journal. https://www.city-journal.org/article/rock-bottom (accessed 11 June 2025).

Husock, Howard (2021).

Archer, Deborah N. (2025). Dividing Lines: How Transportation Infrastructure Perpetuates Racial Inequality. W.W. Norton.

Husock, Howard (2021).